SBVR: Semantics for Business

Recently, Ron Ross invited me to author a regular column on SBVR for the Business Rules Journal. Fact based business requirements specification, structured law and regulation management, knowledge management and education -- integrated at the level of concept definitions, fact types, fact type readings and rules -- has been my professional passion for over 40 years. It has become clear in recent years that semantics, the meaning of business matters, coupled with fact types, fact type readings, and business rules, is at the threshold of a new jump in knowledge worker productivity. After half a century the time has come that semantics will be used to increase knowledge worker productivity substantially through more productive communication and understanding.

From Roman Numerals to Decimal Numbers: a Similar Transition in Knowledge Representation

The acceptance of SBVR[22] will be a major breakthrough in productivity in requirements and knowledge management. It is fundamentally a fact-oriented approach, which makes it comprehensible to many people. "Give business users control. At some point in the process, you will hand over control of all or some of the decision logic to business users in your organization."[32] It so happens that experience with this approach started in Europe in the seventies, and a mature business practice has been developed during the last 35 years. The current version of this practice is called NIAM2007.[17] [18] [19] [20] [21]

What will drive the adoption of this or another SBVR? Economics. The return on investment in practical SBVR is simply too good to ignore. In [15] Tony Morgan states: "...the cost of failure is around $250 billion every year! ... Many research projects have shown that the vast majority of software problems originates from specification error, not from the code as such." It is not any longer a technical or intellectual question. It is a bottom line question. Productivity in banks, insurance companies, educational institutions, most government organizations, as well as major parts of main-stream industries, can increase enormously; probably as good as the industrial productivity increase in the last century, if fact based integrated knowledge management is fully implemented for business communication, specification of business products, business process design, and in education and training.

This adoption will require some time, as it is a major change going from low productivity stovepipes to high productivity integration. The stovepipes of the industrial age will be replaced by integration of the knowledge era. Long ago (in 1987) one could read: "... it is necessary to use some logical construct (or architecture) for defining the interfaces and the integration of all of the components of the system."[36] In Hendryx[12] the following is stated regarding SBVR: "Bravo! This has been a continuous, concerted, interdisciplinary effort of business consultants, logicians, linguists and computer scientists, producing what may be a landmark result in the evolution of business rules and business modeling." It is my expectation that the benefits of SBVR in non-IT related areas far outweigh the IT area. It may nevertheless be expected that SBVR will probably first be used on an industrial scale in business requirements for IT.

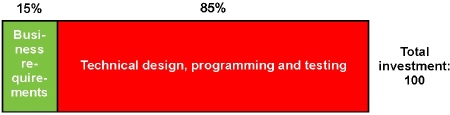

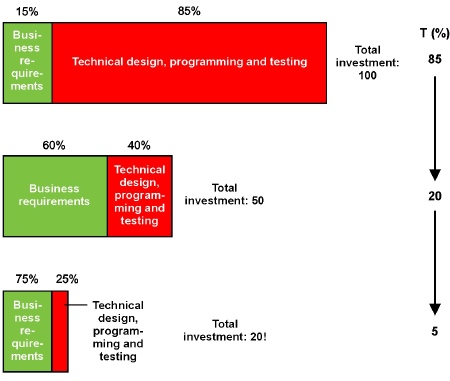

In Figure 1 you see that currently 15 percent of the total IT development costs is invested in business requirements.

Fact based business requirements, according to NIAM2007, consist of the following:

- a list of structured concept definitions, [Aim: to understand each word in a fact]

- a list of the fact types, in which concepts play a role, [Aim: to be able to record facts]

- together with a list of the associated fact type readings, [Aim: to communicate the contents of the recordings in audience oriented formulations]

- a list of the (business) rules, [Aim: to restrict the recordings and transitions of the recordings to those considered useful as well as specifying guidelines for persons how to perform certain duties] and

- a list of the concrete illustrations, [Aim: to promote understanding for all stakeholders and to have sets of test facts at the very beginning of a development project].

The low percentage of 15% of investment in business requirements is a major cause for low productivity in the overall IT and other project cycles. By the way, the concept definition of low productivity is: 'doing with maximum efficiency what should not be done at all'. If you have a better one please let me know.

Figure 1. Traditional IT investment pattern.

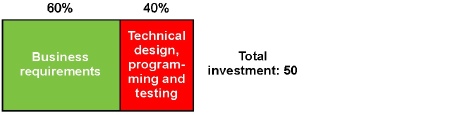

PNA, the company I am associated with, is working in cooperation with a research institute[14] on a new approach in which fact based business requirements is given 60 percent of half the traditional total budget and technical design, programming, and testing the other 40 percent (see Figure 2). The most important point is, however, that the total costs are cut in half. These figures were realized in a recent project for a web based application for 25,000 users and based on 150 relational tables with approximately 1500 columns.

Figure 2. Current reality (2007)

This is the beginning of a new era in which business requirements are properly specified, making extensive use of semantics (structured concept definitions), fact types, fact type readings, and business rules. Our expectation is that a further increase in productivity is possible: the learning curve for widespread adoption of effective business requirements engineering makes it possible to halve the business requirements engineering costs; improvements in software generation will reduce the part of technical design, programming, and testing to 5 percent of the current total development costs. So we expect that the total IT development costs will decrease to 20 percent of the current traditional development costs; 75 percent will be spent on business requirements engineering and 25 % on technical design, programming, and testing. We want to stress that the application area covers data intensive applications, the vast majority of IT applications in business.

The three stages are illustrated below in Figure 3 for easy comparison.

Figure 3. Past, present and future

These figures are staggering. I could give many reasons why I am convinced the third diagram will soon become reality, but the 'soon' will be delayed by the level of unhealthy conservatism, especially in large bureaucracies: "... we need a holistic view on our enterprise. Is it difficult to achieve this goal? Yes, especially for larger organizations because of the change needed to manage this, on top of all other things."[31] I could provide many additional quotes to support this expectation but let me restrict myself to one: "... modeling is finally being recognized as an essential phase of information systems development by a significant and growing number of practitioners, and the expectations are that modeling will become mainstream within the next few years."[10] [9]

The best standard by far for effective business requirements engineering in which the language of the business people is respected and where business people are responsible for the business requirements is, in my opinion, SBVR. My recommendation is to apply SBVR for many applications, including business requirements, knowledge management, business communication, business process design, and education and training. That is the reason why I believe this or another SBVR will become a success, notwithstanding the awkward name. In 10 years we will look back and give OMG credit for starting this new development cycle in structured knowledge management, being applied in many areas, only one of which is IT. I recommend every organization to invest in time in becoming fully proficient in SBVR and to adopt a proven methodology. In that way the business is no longer under the jurisdiction of the mighty colonial power of the kingdom of IT, but can work in a mutually respectful relationship between business and IT. "Many organizations are in trouble ... They have allowed the IT terms involved in developing strategy and running processes to bleed over into product/service vocabulary. The problem is pervasive in the internal business operations of most companies -- something which in no small measure, I'm certain, can be put down as a legacy of traditional IT methodologies."[27]

Another consequence of this approach is: "Business rules are documented and accessible through a repository, no longer hidden in code."[34] The change from 85% to 5% in real dollars is enormous. But it means investing in the activity with the best return. "Industry experts assert that defining user requirements is the most difficult task of software development."[6]

SBVR in a Nutshell

SBVR is an approach that enables people and organizations to treat business, legal, and educational knowledge in a productive way not seen before. SBVR combines the best aspects of logic, natural language, business rules, and conceptual modeling. I like to compare this transition in representation of knowledge to the transition from Roman numerals to decimal numbers. The change in representation brought about a huge increase in productivity.

Business knowledge can be described using:

- a structured business concepts catalogue,

- an associated fact types catalogue, together with fact type readings, and

- the associated (business) rules catalogue.

The business concepts catalogue, provided by SBVR, is a major step forward. "If you have any experience with writing rules, you know the importance of using a consistent vocabulary."[30]

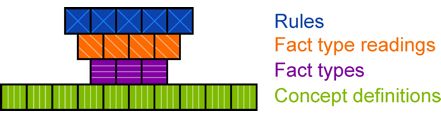

Figure 4 shows very clearly that the foundation of business knowledge is formed by the structured business catalogue, consisting of concept definitions. This set has the largest cardinality. We are collecting statistics from a large number of projects to derive some ratios. As a first approximation, we assume that the average number of roles in a fact type is 3, the average number of fact type readings is 4, the average number of business rules per fact type is 5, and the average number of structured business concepts per fact type is 10. It is amazing to observe that the business concept definition component, both its quality and quantity aspect, has so long been ignored by so many traditional IT methodology approaches. Giving the semantics its proper place by basing fact types, fact type readings, and (consequently) business rules solidly on structured business concept definitions is a major step forward in productivity and understanding. The fact types -- in cardinality the smallest set -- are expressed using the concepts of the business concepts catalogue and verbs. Rules are expressed in terms of fact types. In a future article I will cover the contents with greater precision. In Figure 4 the size of each of the four classes is an indication of the cardinalities; the cardinality of the roles of the fact types is a better dimension than the number of fact types.

Figure 4. The relative size of the knowledge classes

In this series of articles I will provide guidance on how to develop the structured business catalogue, fact types, fact type readings, and rules in such a way that productivity and quality can be controlled using proven business practices. All this is based on a proper subset of natural language and clearly specified and extensively tested procedures, having matured during more than 35 years.

Education and Training

For many years I have experimented, together with a number of other people,[2] [7] [11] [24] [29] [35] with this kind of knowledge description in education and training.[19] This has ultimately resulted in a bachelor education program which is fully based on fact based structured knowledge description. The meta-model aspects are covered in Knowledgatics 101, 102, 103, and 104, all of which are integrated. All further subjects, including all electives, are expressed in concepts described in the 101 through 104. The thesis work is a description of a piece of knowledge or a TO-BE situation resulting in a fact-based business-structured knowledge description that consists of the following:

- A list of structured concept definitions,

- a list of the associated fact types,

- together with a list of the associated fact type readings,

- a list of the associated (business) rules, and

- a representative list of concrete examples.

Laws and Regulations

Extensive study during many years and in several different areas of law and regulations have indicated that this fact based knowledge approach can be successfully applied to enriching text based specifications of law and regulations with structured knowledge.[35] This is a new generation in knowledge management which allows for the subsequent application of various logical operations.

Knowledge Management

The subject of structured knowledge management can be solidly based on fact based knowledge structure and structuring. Hence business requirements, education, business communication, and knowledge management are strongly related and exhibit a considerable overlap.[16] [23]

Knowledge Triangle

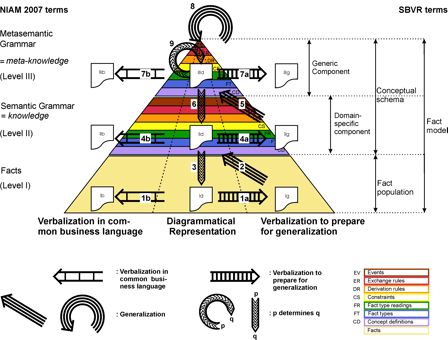

For the past seven years we have been using the knowledge triangle as given in Figure 5.[21] We will use this knowledge triangle in many of the future articles. The knowledge triangle of Figure 5 represents the core concepts of SBVR and a few other concepts, specific for NIAM2007, in diagrammatical coherence.

Figure 5. Knowledge triangle

The knowledge triangle is divided into three vertical lanes. The middle lane represents diagrammatical representations of structured knowledge. The left lane represents verbalizations for business people, which represent the same knowledge in a way familiar to business people. The right lane represents the NIAM2007 'verbalizations to prepare for generalisation', which represents the same knowledge as perceived from the perspective to derive the next level. The latter form of verbalization allows for generalisation, which is a step in the procedure of deriving the next level. This will be shown in detail in a future article.

The knowledge triangle is divided into three levels of knowledge, or facts:

- Facts: facts without a grammatical function, called ground facts in SBVR[22], e.g.,

- 'The operating country Germany uses the business currency Euro.'

- 'The operating country France uses the business currency Euro.'

- 'The operating country USA uses the business currency USD.'

- Semantic Grammars: facts with a domain-specific grammar function, called the domain-specific component of the conceptual schema in SBVR, e.g.,

- 'For each operating country that is recorded, its currency must also be recorded.'

- 'Each operating country name recorded in this fact type has to be unique (i.e., the only occurrence of that name).'

- Metasemantic Grammar: facts with a generic or meta grammar function, called the generic component of the conceptual schema in SBVR, e.g.,

- 'Each fact type must have a role or a sequence of roles for which uniqueness is required.'

Level II contains the rules and concept definitions for ground facts. Level III contains meta-rules, i.e., rules for rules, including the meta-rules themselves as well as the relevant concept definitions. Thus, level III describes itself. Therefore, these three levels suffice for describing structured knowledge.

The triangle was chosen as the form to represent structured knowledge to show that there are always more ground facts than rules for them and more level II (domain-specific) rules than meta-rules. This is the intent of defining rules: rules about knowledge are made to make working with knowledge more productive.

In the knowledge triangle the domain-specific as well as the generic component of the conceptual schema are divided in seven related knowledge classes:

- Concept definitions

- Fact types

- Fact type readings (also known as sentential forms)

- Constraints

- Derivation rules

- Exchange rules

- Events

These knowledge classes are part of SBVR as well as NIAM2007, except for exchange rules and events, which are not part of SBVR. Why are the last 2 mentioned in the knowledge triangle? To facilitate respectful discussions with other communities, such as UML.

Figure 5 can be described in greater detail as follows:

By applying verbalization (1a and 1b) to the diagrammatic representation at the ground fact level (Id, i.e., level I diagrammatic representation), the results are the facts in a textual format (Ig and Ib). By applying generalization (2) to textual representation Ig at the ground facts level, the core of the domain-specific component of the conceptual schema is obtained in a diagrammatic format (IId).

This diagrammatic format of the domain-specific component of the conceptual schema (IId) -- a semantic grammar -- describes the meaning of terms at the ground fact level (Id). It specifies the rules for fact populations (Id) and fact population transitions (Id), and it contains the fact generation rules (IId). Hence IId determines (3) Id and describes its meaning.

Next, by applying verbalization with the aim to arrive at a higher level (4a) to the diagrammatic representation at the level of the domain-specific component of the conceptual schema (IId), we obtain a textual format of the domain-specific component (IIg).

Continuing this process, by using generalization (5) at level II, the result is a diagrammatic representation of a core part of the generic component of the conceptual schema (IIId). This diagrammatic format of the generic component of the conceptual schema -- the metasemantic grammar -- stipulates (6) the semantics and rules for the domain-specific component of the conceptual schema (IId). Again, by applying verbalization with the aim to arrive at the next level (7a) to the diagrammatic format of the generic component (IIId), we obtain a textual representation of a core part of the generic component of the conceptual schema (IIIg).

By applying generalization (8) at level III, the result is the same representation of the metasemantic grammar, i.e., there is no higher conceptual level than level III.

The beauty of (IIId), the generic component of the conceptual schema, is that in effect it stipulates itself (9)!

The result of (4b) and (7b) could be SBVR Structured English. The aim of (IIb) and (IIIb) is to be understandable to persons who do not know the diagrammatical representation but do, of course, know well-expressed English sentences.

The major common ground of SBVR, NIAM2007, ORM, OWL, and FCO-IM are facts. The knowledge triangle uses nine parts to show the coherence between:

(Structured) Concept definitions

The function of the structured concept definitions is to describe at least every word that may be used in a sentence or fact at the layer of (ground) facts[22] in a particular subject and that is new to the student, knowledge worker, or audience. An example is: "A circle is the set of all points in a two-dimensional plane that have an equal distance to a specific point." A structured concept definition may use other words from the same subject, but circular definitions are to be avoided, except with recursion.

Thus, the set of structured concept definitions has a well-defined order, one in which all structured concept definitions only use words that have been defined previously and words supposed to be already known to the reader. The latter is of course context sensitive. The first structured concept definitions in the list are those that use only words that, in the given context, can be assumed to be already known to the reader or audience. This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: What is a/an/the <Concept> or what are we talking about in a certain context? In short: What is it? In Ross[26] we read: "A term is a basic word or word phrase in English or another natural language that workers recognize and use in business communications of all kinds...."

A structured concept definition defines the semantics of a term. Structured concept definitions were given their proper place since the mid-nineties in NIAM2007. After 12 years of experience with systematically applying structured concept definitions in business practice, at PNA we have come to the conclusion that Structured Concept Definitions are the most essential part when semantics is considered important. I am happy to read in Ross: "In fact modelling everything eventually comes around to developing good definitions."[26] In future articles I will provide the concept definitions of the core of SBVR and NIAM2007 metaterms.

The value of Structured Concept Definitions is gradually being recognized. In O'Neal[23] I read: "One firm went through a long and painful migration to a combination customer relationship management (CRM) and financial management package, consolidating hundreds of small and large legacy systems. Each system had its own vocabulary and semantics, as did the new CRM package. How could everyone be trained to speak the same language? The obvious answer was to create a business glossary."

"A central idea of the business rules approach is that business rules should be expressed with business people in natural language."[28]

Fact types

The function of a fact type is to function like a data structure and to make it possible to record data, facts, or declarative sentences. An example of a fact type is: Of a country the capital is recorded. More formal in a fact type reading[22] in NIAM2007 notation: Country <Country> has as capital <City>. Between each couple < > is a placeholder that needs to be filled with concrete terms to get a fact; e.g., 'Country The Netherlands has as capital Amsterdam'. A second example: Of a country is recorded which languages are spoken.

The recorded data can be perceived as the variable parts of otherwise equal sentences. This perception is expressed in sentence patterns called fact type readings in SBVR.[22] This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: Which business facts are recorded about it?

I recommend incrementally specifying the structured concept definitions and fact types before the business rules. Why? A business rule builds upon a fact type. In Ross[25] I read: "In business problems involving hundreds or thousands of rules -- not at all uncommon -- there is no way to achieve consistency across such large numbers of rules without a common base of terms and facts." I would like to add: in many businesses the hundreds or thousands of rules are deeply buried in encodings unclear to the business person. One day the world might realize this problem and start a gigantic archeological expedition into the two countries called Procedural and Object Code.

Fact type readings

Fact type readings facilitate the communication about the contents of the fact population. Two examples of fact type readings:

- 'The country <Country> has the city <City> as its capital.'

- 'In the country <Country> among others the language <Language> is spoken.'

Thus, fact type readings, or sentence patterns, describe all possible sentences at the facts population layer. This knowledge class also enables the use of different natural languages for the same contents of the facts layer. For example:

- 'Le pays <Country> a comme capitale <City>'.

- 'Das Land <Country> hat als Hauptstadt <City>.'

This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: How are the business facts communicated when using an easy-to-understand language targeted at a certain audience?

Constraints

The function of a constraint is to restrict the contents of the facts layer and its transitions to those that are considered useful. E.g., a constraint would prohibit such sets of sentences as: 'Bill Clinton was born in Arkansas and Iowa.' This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: Which restrictions apply to the populations of business facts and their transitions?

Derivation rules

The function of a derivation rule is to derive new sentences from sentences existing in the layer of facts. E.g., if we know for persons in which country they were born, a derivation rule can produce sentences which state how many persons were born in a country. This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: How are certain business facts established?

Exchange rules

The function of an exchange rule is to move sentences from the outside world into the system, or the layer of facts, or remove sentences from the layer of facts. This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: How are the contents of the fact population inside the system altered?

Events

The function of an event is to notify when a certain derivation rule or exchange rule needs to get started. This knowledge class gives an answer to the following question: When are the business facts established or altered?

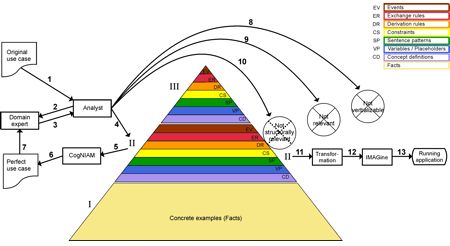

Adding business analysis processes

In a practical project the knowledge triangle (the structure) needs to be extended to include the analysis of business processes. The start is with a use case, usually business process oriented and in most cases:

- fairly incomplete,

- fairly redundant,

- fairly inconsistent and

- fairly indeterminate.

The analyst applies the fact-oriented methodology to specify in iterations the complete set of fact type readings, fact types, constraints, and the structured concept definitions. The cycle 5, 6, 7, 4, <2,3> in Figure 6 is repeated until all the incompleteness, redundancies, inconsistencies, and non-determinations have been removed. The software used -- CogNIAM -- generates a natural language text for the seven knowledge classes, thereby preventing the need for the business domain expert to read fact type diagrams; this is an example of one kind of verbalization. What is modeled in the fact orientation tool is an answer to the following questions as mentioned previously for the respective knowledge classes:

- What is it?

- Which business facts are recorded about it?

- How are the business facts communicated when using an easy to understand language?

- Which restrictions apply to the populations of business facts?

- How are certain business facts established?

- How are the contents of the fact population inside the system altered?

- When are the business facts established or altered?

These seven questions turned out to be fairly convincing in the business environment.

Next, two questions are practical for organizational purposes:

- For which person or organization are the business facts established or altered?

- By which person or organization are the business facts established or altered?

Structure

By having all relevant aspects defined and facts about them and rules about facts stored, it becomes possible to start using measurements in business rules and knowledge management. My experience over the last 10 years has indicated that knowledge metrics can play a very useful role in improving the bottom line. "Constructing a connected measurement system is critical for us to break down overall targets into what people do every day."[4]

Figure 6. Knowledge Triangle, Including the Business Analysis Process

The Economics of SBVR: Why Do I Recommend That All Businesses Should Invest in SBVR NOW?

The productivity in knowledge management, business requirements engineering (including the use of business rules), business communication, all kinds of knowledge work, and the vast majority of education could be substantially improved if based on SBVR and combined with a methodology proven in business practice. In Vanthienen[33] I read: "Business rules and [author: (decision)] tables can be used to model and apply regulations, procedures and various kinds of complex business decisions and calculations."

SBVR models can be used for many purposes. One is to function as the common business vocabulary and specification of all facts of interest to the business and all rules that apply to these facts. In Hall[8] I read:

What could you do with the model?

With suitable tools:

- Send it to other parts of your company, or to close partners

- Store it in your repository, as guidance for your business, and

- Manage it over time, as your business vocabulary and rules change

- Validate and verify its content

- Use it as a basis for creating consistent, focused guidance for different groups of people in your company, business partners, customers, suppliers...

As SBVR models covering a substantial and gradually increasing part of the business become very large, there is the same reason for software support as there was when automating accounting or business processes like ordering and shipping. In Baisley[1] the wide applicability of SBVR is shown by using it for authorization.

SBVR models could be productively used to describe most, if not all, subjects in business education. SBVR models can be used as a basis for software generation. "When each business rule category becomes the basis of software that uses the business rule documentation to generate an application portfolio component to enforce that statement, what we have formerly expressed as metadata will be used to generate application components. At that time -- when metadata is routinely used to generate executable business rules -- the definition of metadata will be 'the representation of business rule statements according to a classification scheme that can be readily transformed into business information systems'."[16]

SBVR Methodology

SBVR is methodology agnostic. The professional world is invited by the SBVR committee to come up with productive methodologies. Wide innovation and value-adding software development in the area of compliant notations is encouraged. In a free world the best will survive. "The key and the challenge is knowing how to gather and manage business rules from the business perspective and how to connect them to technology implementations."[13] In a future series of articles I will present a complete methodology (NIAM2007) for SBVR based on 40 years of business experience with fact modeling and completely integrated with business processes and business communication. In that methodology the language used is the language of the business and as close as possible to natural language. In Chapin[5] I read with pleasure: "SBVR users are strongly encouraged to limit the amount of internally managed vocabulary, and use everyday natural language as much as possible, backup with a standard dictionary...."

Part of a good methodology is the structure or architecture of the entire fact castle. In a future article we will demonstrate by applying the conceptualization subprocess 'Verbalization type II' that there are exactly three levels of facts as is assumed in SBVR. Verbalization type II is a verbalization of information-bearing constructs with the aim of deriving the core part of the next level grammar. This is different from Verbalization type I (except at the level of ground facts), whose aim is to make a fact type or rule available in language understandable to the business person.

"What is needed is a formal process of improving the capability, including updating the rules and the enablers within which they are embodied or embedded. This Improved Guidance Creation Process will require resources and a commitment in a process-managed environment. With new rules published and communicated regularly and with enablers renewed regularly, improved performance will be delivered, staff will continuously learn, and the organization will adapt and thrive."[3]

References

[1] Baisley, Don, Unisys Rules Modeler, European Business Rules Conference 2007, slide 13.![]()

[2] Bollen, Peter, Using Fact Orientation for Instructional Design, Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Herrero, P. e.a. (eds), OTM Workshops 2006, LNCS 4278, 2006, pp. 1131-1141.![]()

[3] Burlton, Roger, Business Process Management: An Improved Guidance Creation Process, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 6, No. 9, Sep. 2005, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2005/b248.html.![]()

[4] Burlton, Roger, Best Practices of Process Management: The Top Ten Principles (part 1), Business Rules Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1, Jan. 2006, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2006/b269.html.![]()

[5] Chapin, Donald & Hall, John, Semantics and Business Rules, Presentation at Semantic Technology Conference, San Jose, California, March 2006, slide 18.![]()

[6] Gottesdiener, Ellen, Eliciting Business Rules in Workshops (part 1), Business Rules Journal, Vol. 3, No. 11, Nov. 2002, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2002/b121a.html.![]()

[7] Gutknecht, Mario, Promising Chance of Innovation for Conceptual Modeling in Commerzbank, Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Herrero, P. e.a. (eds), OTM Workshops 2007, (to be published).![]()

[8] Hall, John, Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules (SBVR), Presentation to MARS/RTESS & SwA OMG Boston, June 2006, slide 15.![]()

[9] Halpin, Terry, Information Modeling and Relational Databases, Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco, 2001.![]()

[10] Halpin, Terry, Modeling Concepts: Setting the Scene, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 3, No. 12, Dec. 2002, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2002/b126.html.![]()

[11] Hansen, Joe & Dela Cruz, Necito, Evolution of a Dynamic Multidimensional Denormalization Meta Model Using Object Role Modeling, Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Herrero, P. e.a. (eds), OTM Workshops 2006, LNCS 4278, 2006, pp. 1160-1169. ![]()

[12] Hendryx, Stan, OMG Business Rules Proposal Nears Completion, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 6, No. 2, Feb. 2005, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2005/b226.html. ![]()

[13] Lam, Gladys S., Plainly Speaking: What Is a Rule? Business Rules Journal, Vol. 4, No. 5, Sep. 2003, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2003/b149.html. ![]()

[14] Luursema, Eddy, van Bers, Arnoud & Nabben, Misja, IMAGine, paper presented at Conference Information Systems: The Next Generation, Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2007. ![]()

[15] Morgan, Tony, Business Rules and Information Systems: Aligning IT with Business Goals, Addison-Wesley, Boston, 2002. ![]()

[16] Moriarty, Terry, What is metadata? Database Programming & Design, July 1997, p. 5. ![]()

[17] Nijssen, Sjir, On the Gross Architecture for the Next Generation Database Management Systems. In: Proc. IFIP'77, 1977 IFIP Working Conf. on Modelling in Data Base Management Systems, ed. B. Gilchrist, 327-335: North Holland Publishing Company, 1977. ![]()

[18] Nijssen, Sjir, A Framework for Discussion. In: ISO/TC97/SC5/WG3 and comments on 78.04/01 and 78.05/03. ![]()

[19] Nijssen, Sjir, A Framework for Advanced Mass Storage Applications, Proceedings of the MEDINFO 1980, Tokyo, The world conference on medical informatics, 1980. ![]()

[20] Nijssen, Sjir, On Experience with Large-scale Teaching and Use of Fact-Based Conceptual Schemas in Industry and University, In Proc. DS-1'85: IFIP WG 2.6 Working Conference on Data Semantics, eds. T.B. Steel and R. Meersman, 189-204: North Holland Publishing Company, 1986. ![]()

[21] Nijssen, Sjir & Bijlsma, Rita, A Conceptual Structure of Knowledge as a Basis for Instructional Designs, Proceedings IEEE Conference on Advanced Learning, 2006. ![]()

[22] OMG, Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules (SBVR), First Interim Specification, Mar. 2006. Available as dtc/06-03-02 at http://www.omg.org. ![]()

[23] O'Neal, Bonnie, Why Bother to Capture Business Metadata? Business rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 7, July 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b354.html. ![]()

[24] Piprani, Baba, Using ORM-Based Models as a Foundation for a Data Quality Firewall in an Advanced Generation Data Warehouse, Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Herrero, P. e.a. (eds), OTM Workshops 2006, LNCS 4278, 2006, pp. 1148-1159. ![]()

[25] Ross, Ronald, Principles of the Business Rules Approach, Addison-Wesley 2003, p. 69. ![]()

[26] Ross, Ronald, Business Rule Concepts, Getting to the Point of Knowledge, Business Rule Solutions LLC, 2005, pp. 11, 51. ![]()

[27] Ross, Ronald, Are IT Terms Fundamental to Every Business? Not! Business Rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 6, June 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b349.html. ![]()

[28] Ross, Ronald, What's Wrong with If-Then Syntax For Expressing Business Rules ~ One Size Doesn't Fit All, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 7, July 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b353.html. ![]()

[29] Rozendaal, Jos, Industrial Experience with Fact Based Modeling at a Large Bank, Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Herrero, P. e.a. (eds), OTM Workshops 2007, (to be published). ![]()

[30] Seer, Kristen, Business vs. System Thinking in Rule Writing, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 9, Sep. 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b361.html. ![]()

[31] Spreeuwenberg, Silvie, Flexibility and Business Rules, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 9, Sep. 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b363.html. ![]()

[32] Taylor, James & Raden, Neil, The Need for Smart Enough Systems (Part 3), Business Rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 9, Sep. 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b365.html. ![]()

[33] Vanthienen, Jan, What Business Rules and Tables Can Do for Regulations, Business Rules Journal, Vol. 8, No. 7, July 2007, URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2007/b355.html. ![]()

[34] von Halle, Barbara, Business Rules Applied: Building Better Systems Using the Business Rules Approach, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002. ![]()

[35] Vos, Jos, Is there Fact Orientation Life Preceding Requirements? Meersman, R., Tari, Z., Herrero, P. e.a. (eds), OTM Workshops 2007, (to be published). ![]()

[36] Zachman, John, A Framework for Information Systems Architecture, IBM Systems Journal, 26(3), 1987, pp. 276-292. ![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.