SIPOC for Service — Is It Enough?

SIPOC is an acronym for Supplier, Input, Process, Output, and Customer. The concept has been made popular by the Supply Chain process groups and Six Sigma. It was designed specifically for manufacturing organizations. Today, many service organizations are using (or attempting to use) this approach for defining and documenting service processes. It's important to understand whether it's an adequate process modeling notation for service processes.

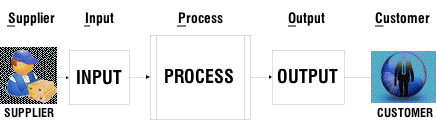

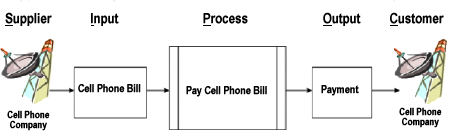

Figure 1, the SIPOC Diagram, represents the basic concepts of the SIPOC notation.

Figure 1. Basic Concepts of the SIPOC Notation

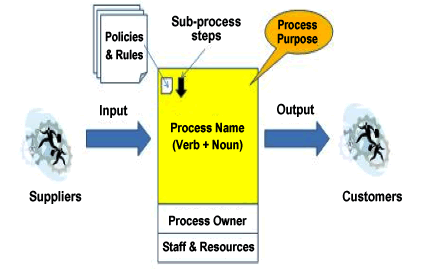

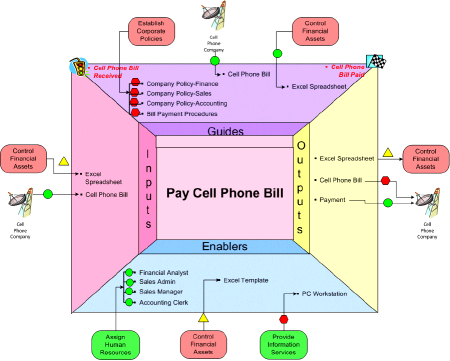

In addition to the basic concepts of SIPOC, the diagram in Figure 2 also presents how 'policies & rules', process purpose, process owner, and staff & resources can be documented.

Figure 2. Additional Concept Types

In order to evaluate the usefulness and appropriateness of applying the SIPOC modeling notation to the documentation of service processes, it's essential to understand some of the basic concepts of that modeling notation. There are three aspects of SIPOC as it relates to the "service industry" or "service processes" that will be considered in this article: first, the SIPOC definition of process as beginning with a Supplier and ending with a Customer; second, the SIPOC definition of 'inputs' and 'outputs' as the most important components of understanding a process flow; third, the SIPOC approach to defining "Process Scope" or "Boundaries" of Processes. There are other aspects of SIPOC that should be clearly understood before applying it to service processes, but those will be the topic of another article.

Supplier vs. Customer

First, the SIPOC notation is based on the idea that a process starts with a supplier and ends with a customer. The concept of supplier vs. customer in a service business can be confusing. Modeling processes can be very simple or complex. Complexity normally results in less understanding.

In order to understand the 'real' opportunities for improvement in a process, there must be a clear understanding of where value is created. Service businesses are normally thought of as organizations that create or enhance a service to a customer in order to deliver value to that customer. The supplier of the service is the business itself. Trying to define a supplier for a service is a manipulation of a concept in an attempt to fit a service process into a modeling notation developed for manufacturing.

The vocabulary of "supplier" verses "customer" may not seem important but just the effort to define a supplier may create more confusion than it adds in clarity. In a service process, there is a customer who has a need for help (service) and there is an organization that provides that help (service). In a service process, the life cycle is from customer to customer, not supplier to customer as in manufacturing. Another way to express the concept is to think of it as a full circle. The circle is not complete until something of value is delivered to the customer in response to a request from the customer.

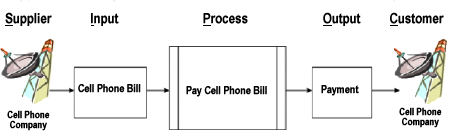

The most important aspect is that whatever vocabulary is used, a better understanding of the process should be the objective. This concept is represented in Figure 3, where it more accurately shows the process starting and ending with the same stakeholder.

Figure 3. SIPOC Diagram

Completeness of Process Information

Secondly, the SIPOC notation focuses on inputs and outputs with regard to a process flow. In fact, these are only two of four categories of information that are critical to an understanding of a process. The two elements missing from the standard SIPOC model are the categories of Enabler and Guide.

Enablers provide information related to who and where of a process. Enablers are the people, tools, and facilities that are necessary for the transformation of the input to an output. They can also be thought of as the things that must be present to add value in a process.

It is essential that enablers be documented separately from the transactional "flow" through the process. When they are documented as part of the flow, it becomes difficult to understand the difference between the "process" flow and the "system" flow. This type of modeling confuses the business user by incorporating aspects of both a system flow and a business process flow but not complete information for either. Therefore, the model's usefulness is compromised due to a lack of clarity since it's neither a true business process flow nor a system flow.

Guides provide information on how, why, and when of a process. For example, Guides are the events that define the boundaries of the process. The "triggering" or "starting event" designates the beginning of the process, and the "ending" or "closing" event designates the ending of the process.

In addition, guides are the policies, procedures, knowledge, experiences, and even measures that drive the decisions that are made in a process. Guides also include 'rules'. In generic definitions of SIPOC, it is suggested that rules should be included along with other "things" as inputs to the process. The problem is that the rules don't get changed by the process but rather are used as the decision logic of a process.

In order to conduct an efficient and effective analysis of a process, it is necessary to separate the changes in state from the criteria that create those state changes. The majority of real problems in a process are not the result of the changes that occur but rather the criteria that initiate and drive those changes. At least 80-85% of the time, it is the guides/rules that need to be changed in order to solve the real problems of efficiency, effectiveness, and agility in the process.

Changing the cause of the problem (rules) and not the symptoms (input/output) provides an organization with opportunities to significantly reduce process cycle times as much as 15 days to 45 minutes or 12 days to 30 seconds. Dramatic changes like this are rarely possible without changes to the 'rules' that drive the process. In order to identify opportunities to change the rules they must be clearly separated from the "flow" of the process. Therefore, it's best to consider guides as a separate component when documenting the process. This will also create a more maintainable process model for the future.

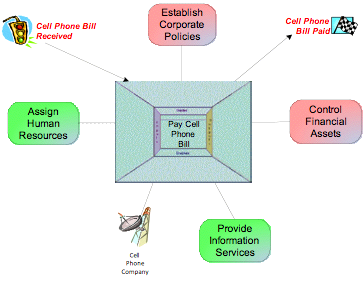

Figure 4. IGOE Diagram

Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the difference in information available about the process using an IGOE approach versus a SIPOC approach. Figure 4, the IGOE diagram, provides a complete picture of all the components of information necessary to perform the process including the when, why, how, who, and where information. Figure 3, the SIPOC diagram, provides a very limited view into what's necessary for the process. Notice there is no information on why, how, when, who, or where in the SIPOC diagram.

Definition of Process Scope and Project Boundaries

Thirdly, using the SIPOC notation to define the boundaries of service processes provides very little information for Process Owners and Project Managers. It is claimed that it provides Process Owners with a high-level understanding of the boundary of the process. In reality, SIPOC actually provides very little information regarding the boundaries of a process or information that is helpful in evaluating the scope of a process project. In a SIPOC model, there is no information regarding potential impact to other areas of the organization. See Figure 3.

A more precise approach to defining process boundaries and project scope is to start by understanding/defining the events in a process and gaining consensus on which will be considered the "beginning" and "ending" events. These are the boundaries of the process. The next step is to identify the stakeholders of the process. These are the sources or destinations for information/things that make up the process. This can be determined by inquiring of the people in the process where they receive information/things from and where they send information/things to when they have finished working on them.

It is also critical to understand any relationships that exist between the process and external entities/stakeholders such as customers or suppliers. This creates what is called a "process context diagram" because it illustrates the context of the process in an organization to both internal and external entities, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Process Context Diagram

Once the stakeholders — both internal and external — are known, then additional information about this process (such as Inputs, Guides, Outputs, and Enablers) can be identified at the high level. Figure 6 is an example of a diagram containing this type of information. It is usually called a High-Level IGOE Stakeholder Diagram.

Figure 6. High-Level IGOE Diagram with Stakeholders

This diagram provides very useful information to Project Managers and Process Owners regarding all elements of the process and the impact that changes to the process might have on other areas of the organization.

Next, as part of determining the size or scope of the project, the major problem areas should be identified. Using the information in Figure 6, project managers, process owners, and SMEs can conduct a high-level, relatively accurate root cause analysis to determine the focus and scope of the improvement project.

A technique called a "health check" is a very effective method for conducting this high-level root cause analysis. A simple 'red', 'yellow', and 'green' dot method is used. Red indicates a serious performance problem. Yellow indicates a minor problem or an opportunity to improve the process. Green indicates that everything seems to be in order with no need for change. Once consensus has been reached, a very accurate definition of the scope of the project can be agreed and resources committed.

Figure 7. High-Level IGOE Diagram with Stakeholders and Health Check

Project managers could start with this level of information or use the SIPOC diagram in Figure 3.

Figure 3. SIPOC Diagram (repeated for comparison)

It's very important to understand that process projects are "rarely" limited in scope to "one" process. Admittedly, they don't often start as more than one process, but as more information is uncovered about the process, the project will suffer from what is often referred to as "Scope Creep." Scope Creep is a change in size and often focus of the project.

Since the two major factors contributing to the success of any project are time/$$ and resources, changes in scope most often effect both of these components, resulting in a need to compromise the quality of the deliverables for the project. Most scope creep is the result of an awareness of more information about the process. Therefore, the more information project managers and process owners have when they define a project, the less likely it is that major changes in scope will occur.

The fact is that a SIPOC model or method would unfortunately provide the Process Owner with very limited information for determining project scope, resulting in a greater risk of major scope creep. The SIPOC diagram communicates what's going in and out of the process. However, because policies and rules can be included in this information, it's often difficult to determine where value is really being created. In addition, there is no information regarding the relationship one process has with another. The result is a lack of knowledge regarding the impact that changes to the process may have on other areas of the organization and major changes in project scope.

Conclusion

When all three aspects — customer vs. supplier definition, the completeness of the process information, and the information available to accurately and objectively define the scope of a process and project — are considered, using a SIPOC modeling approach for documenting service processes is dramatically inadequate. When so much more information is available and there are techniques for documenting and communicating that information more effectively, those techniques should be utilized.

SIPOC has its place in the manufacturing industry. Hopefully, this article will help clarify some of the reasons SIPOC is not complete enough to be a good method for documenting and understanding service sector processes.

Other aspects of SIPOC will be discussed in a future write-up. Remember, the most important concern is not specifically 'how' a process is modeled but rather an accurate and clear understanding of the process and the opportunities to improve the process.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules