Business Architecture Essentials: Defining your External Stakeholders: Interactions, Value, and Performance

Introduction

In the first article of this series, I discussed the current interest in Business Architecture that has been brewing in the last little while and also discussed some of the frameworks that professionals have been looking at for guidance and inspiration. The first article was intended to provide an overview of the field and it introduced an overarching set of concepts that we in Process Renewal Group have been successfully using to classify and categorize issues of concern. In the second article I tackled the challenge of scoping your architecture and the usefulness of selecting what's in and out, based on value chains.

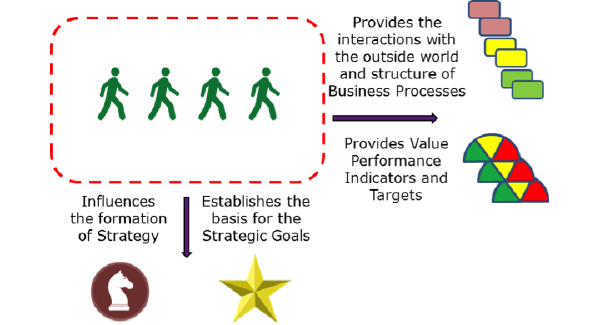

The Process Renewal Group model, which is the origin of the BPTrends methodology, was originally formulated in the mid-nineties and has undergone continuing evolution for twenty years to sustain itself as a modern way of designing a business. It incorporates the best practice of a number of approaches combined with other ideas that have stood the test of time as well as some of our own and others' innovations. Within the past year it has been subject to a significant update to connect traditional and new ideas into a comprehensive Business Architecture framework and methodology as depicted in Figure 1. The diagram shows the main logic of the discovery and design process. Please note that the diagram that articulates the concepts has changed slightly from previous articles based on more feedback and experience in its usage. All that has happened is the swapping of position of Business Performance Indicators with Business Capabilities to show a tighter alignment between Processes and Capabilities.

Figure 1. The Process Renewal Group model.

Given that in an architectural initiative we should have by now gained agreement on the scope of inclusion of the value chain(s) to be addressed we can now move to understand who cares about what we have chosen to do and what is important for relationship and business success.

In this analysis we continue to view the organization as a black box for now to ensure we know what the value expectation is for all of those external entities that we serve or that serve us. We are trying to keep the end in mind by first of all defining what the desired end is and looking at how well we and the stakeholders are performing relative to it. The premise is that stakeholders have an interest in one or more of the organization's value chains. They give things to and get things from them. They have expectations of us in terms of both satisfying their needs and having an easy experience. We have the same from them.

In this analysis we continue to view the organization as a black box for now to ensure we know what the value expectation is for all of those external entities that we serve or that serve us. We are trying to keep the end in mind by first of all defining what the desired end is and looking at how well we and the stakeholders are performing relative to it. The premise is that stakeholders have an interest in one or more of the organization's value chains. They give things to and get things from them. They have expectations of us in terms of both satisfying their needs and having an easy experience. We have the same from them.

What does the Stakeholder Model give us?

Knowledge documented regarding stakeholders provides the context (start and end) of the processes we conduct, defines the ultimate capabilities we need to have to be able to attain results, and helps us formulate the right balance in our strategic intent, reconciling a number of perspectives that may otherwise be in competition with one another.

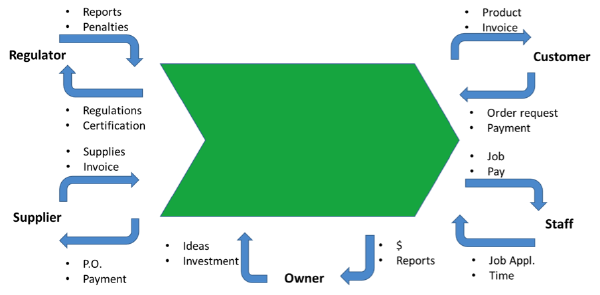

Figure 2. The purpose of the stakeholder analysis activity.

The purpose of the stakeholder analysis activity is depicted in Figure 2. To capture all we need, we must gather knowledge or insight regarding the following:

- Who are the stakeholders of note? Who cares, and who do we care about?

- What tangible or virtual exchanges do we have with them?

- What expectations do we have of them and them of us? What value and experience is expected by both parties?

- What measurement indicators can be used to evaluate performance, and what are the gaps between current state and future objectives?

- What aspects of the relationship are unhealthy?

- What are the required capabilities for relationship success?

We will look at each of these in order.

Who are the stakeholders of note? Who cares, and who do we care about?

The first questions to be answered regarding external connections are 'Who do we care about?' and 'Who cares about us?' Some stakeholders interact with us on a regular basis and exchange things with us. Some stakeholders may not interact with us much but certainly affect what we do or are affected by what we do. Others may be interested but are not as involved as the first two groups. We need to care about all of them and get them to care about us in the way we want. Once we understand them we can decide what we need to do to optimize our part in the ecosystem within which we all participate. It all starts with gaining agreement on the classification of the various types of stakeholders that we wish to see. Be aware that the stakeholder segmentation names assigned and their definitions can be a source of major semantic, cultural, and political dissonance.

The first thing to do is to structure the stakeholder types that we serve. This can be tackled by looking at customer segmentation, by products or service types, by business volume, by the nature of how direct or indirect the relationship is, or by other considerations that may be unique to the business or common in the industry. This can be as much art as science and reflects thinking that may have been done about strategic intentions regarding markets and trends. Once we have a good handle on the customer segmentation, we can look at other stakeholder types and sub-types.

Some considerations on the generic highest levels of stakeholder types are:

- Customers and Consumers: those we are in business to serve.

- Owners: those who invest in or direct our activity.

- Suppliers: those who provide products, services, and resources to us.

- Staff: those who work on serving and supporting the enterprise value chain and its stakeholders.

- Community: those who govern, guide, or influence what and how we do what we do.

- Competitors: those who fight in our markets for our customers and/or their budgets.

- Enterprise: the enterprise itself.

- Overlaps and Oddballs: those who play conflicting roles.

This category is often not as simple as it may seem since there may be direct customers with segmentation such as large and small, intermediaries or channels to market such as distributors or resellers, consumers of our offerings sold through other organizations, differing recipients of specific types of products and services in differing geographies or different markets, and different roles played by buyers, influencers, and users. We have to catch them all and describe them in a way that all can agree since our processes must deliver to each and we have to be able to do so.

This category includes all the investors, boards of directors, and senior executives. Again there will likely be sub levels depending on degree of control. It will be different for different types of industries, public sector organizations, and different countries' legal requirements.

Suppliers may be considered a generic type of stakeholder or be differentiated according to what they supply so long as the supply process is different. Buying office supplies may be handled quite differently than purchasing software or agreeing to and executing an outsourced operation.

Staff is considered to be an external stakeholder type since members join the enterprise voluntarily and will thus need to be personally attracted and subsequently assume internal roles once hired and remain satisfied to be retained. There may be several types based on the longevity of their tenure or association with collective bargaining units.

This can be a very broad category with many segments since those who provide regulatory and compliance requirements and certification will be different from those who may be simply influencers on us or for us. This can include geographic-based, professional-based, or industry-based relationships. Environmental stakeholder considerations are sometimes grouped under stakeholder types, such as the planet, as a convenience.

Competitors may be targets for capacity enhancement by acquiring them or they us. They may also be collaborators under certain conditions.

This category is somewhat esoteric in that it considers the enterprise to be a different stakeholder from its staff, owners, or customers because its perspective is one of sustainability beyond the short term and freedom to act in the best interest of the organization's longer-term health.

There will always be other types that do not fit neatly into the customary categories. There will also be those that play multiple roles, such as customers or suppliers that compete with you or competitors that own part of your company, for example.

Figure 3. Structure the stakeholder types served.

These categories are all decomposable into sub-types, but there is a practical limit to over refining beyond the point of usefulness for enterprise-level work. Each type can also be weighted so that some will be considered more heavily when it comes to influencing strategic choices and capability design decisions. For example, should the five customers that make up seventy-five percent of your business volume be given equal weight as the thousands who make up the remaining twenty-five percent? If you choose not to weight them, you actually are weighting them by making them all equally important strategically. Is that what you want?

What tangible or virtual exchanges do we have with them?

A great way to start to understand the outside stakeholders and to determine what we must do and be good at doing is to build a value chain context diagram. It is the least politically challenging of all the stakeholder work. Such a diagram is essentially a model of stakeholder interactions and exchanges represented by drawing a simple diagram of the actual and planned exchanges delivered to and received from each stakeholder type, using our 'Value Chain in Focus'. Clearly, inside the box there are a lot of activities that must somehow come together to take what comes in and make what goes out a reality. This staring point is the only real way to find your end-to-end business processes from a value point of view. These are your business processes, like it or not, quite independent of the organizations that do them or the tools you use. Sometimes they work well and other times they don't. We can show all exchanges including:

- Products delivered or received

- Services provided or received

- Information exchanged

- The results of decisions made

- Knowledge shared

- Commitments (formal and informal) made

- State changes of various assets or relationships

When building a context model, we expect to find that an incoming item will often be paired with one or more outgoing exchange items. For example, a request for credit may come in, and a rejection or acceptance (result of a decision) may go out in response, along with instructions on what to do next.

Figure 4. A value chain context diagram.

What expectations do we have of them and them of us? What value and experience is expected by both parties?

A useful technique for sorting out the stakeholder vision is called Time Machine Visioning. In this 'back to the future' scenario, the architect and strategist imagine themselves arriving at the future they would like to see at the planning horizon when all results are in place and the processes are all performing as desired (the ideal world). Statements are postulated to reflect the expectations that each stakeholder type would have or, better yet, what you want them to have. It then becomes the value chain's role to do everything necessary to make the statements come true. These are referred to as stakeholder expectations and are indeed our goals for the relationship.

The technique defines value and experience expectations that work as criteria to keep everyone aimed squarely towards the purpose of any necessary changes. The criteria must be used as the guide when making business design decisions or choosing among a number of options. This is not to say that all stakeholders will love what we want for them, but since it is our business we must choose the criteria or it will be done by those with the most power internally.

Figure 5. Time Machine Visioning.

What measurement indicators can be used to evaluate performance, and what are the gaps between current state and future objectives?

The stakeholder expectation statements are the basis for the determination of the performance indicators required to be able to monitor success of the relationship and progress towards success. These statements will now transform into contributing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) towards the strategic intent statements and should be directly linked to them. They measure value creation from the perspective of the stakeholder as well as the value chain itself. Both sides must realize value from the relationship to attain its expectations. These will be a combination of effectiveness (such as net promoter score), efficiency (such as cost per transaction), quality (such as % compliance to standards), and agility (such as time to market for new products). To avoid sub-optimization, one KPI will not do. Some combination of these is more realistic even if somewhat conflicting.

The goal statements are also the basis for establishing the measurable relationship objectives. These objectives, by definition, are the target values of the KPIs that the organization or value chain will aim for. They will be set for the same timing as the time machine destinations. They may also be established for interim points in time as milestones to be achieved along the way. These KPIs and targets can now become part of a scorecard at the next level down, which in turn will be supported by traceable process measures that will be derived from the process architecture at the next level below that.

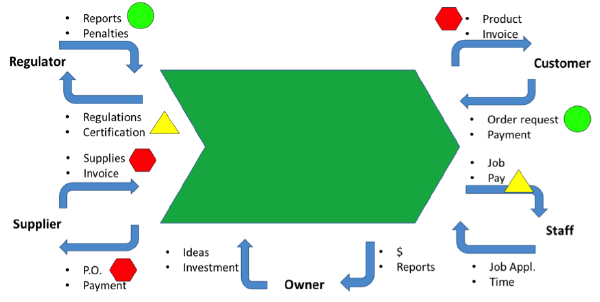

What aspects of the relationship are unhealthy?

Once we know what the value and operational drivers are of the stakeholders involved, a triage-like assessment of the good (green), bad (red), and in-between (yellow) health of each exchange can be made. This will give us a good start on understanding likely relationship issues and opportunities that have to be dealt with. Taken together it becomes obvious which relationships are in good health overall and which need serious attention in terms of the processes that support them or are supported by them. A form of strategic Ishikawa or Fishbone diagram is produced, but the real value of the exercise lies in the common insights gained across a typically diverse and siloed group of internal decision makers, discussing the situation from a range of perspectives.

Figure 6. Making an assessment of the health of each exchange.

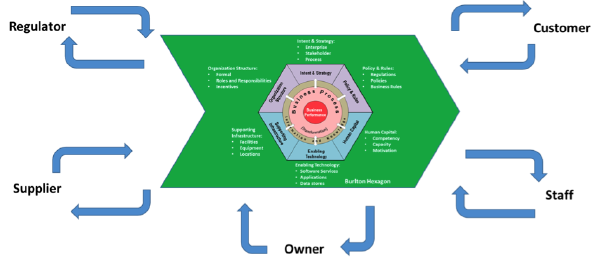

What are the required capabilities for relationship success?

The gap between current versus target objectives will indicate the state of the relationship and the extent of capability changes needed. Typically the changes will be greater and more capabilities will be affected when the performance relationship gap is larger. Small performance gaps will not require launching major new systems but a big gap may. Small gaps will not require significant organizational changes but large ones may depend on them.

In order to discover the new capabilities required, make sure you answer the following question: "In order to achieve our vision and improvement targets from where we are today, what is it that is absolutely vital to have in place?" Determine the responses from the perspective of each stakeholder type. Use the Burlton Hexagon to derive the various attributes of new capability required.

Figure 7. The Burlton Hexagon, used to derive the various attributes of new capability required.

Future Articles

Taken together, the results of the stakeholder analysis will provide additional strategies and criteria for later decision making as well as the beginning of the design of the process architecture. There will be conflicts among stakeholder perspectives that will have to be sorted out. It is critical that these conflicts be addressed and resolved as part of our strategy formulation (which will be covered in our next article) rather than later when inconsistencies are typically discovered, much later in process analysis and capability development.

That's the way I see it.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules