Being Unambiguous Beyond Reasonable Doubt in Expressing Rules

Extracted from Rules: Shaping Behavior and Knowledge, by Ronald G. Ross, 2023, 274 pp, https://www.brsolutions.com/rules-shaping-behavior-and-knowledge-book.html

By 'being unambiguous' let me be sure you know exactly what I mean. I do not mean being unambiguous beyond all doubt in every aspect of natural language. You'd be surprised how often people think that's what I mean when I talk about eliminating ambiguity. No! I stipulate up-front that's impossible (and probably not even desirable).

So, let me be very clear then about the context of this discussion.

- First, I am talking only about rules and other forms of guidance for business and government.

- Second, I assume a structured business vocabulary, such as one based on a concept model. Without a blueprint to go by, all bets are off.

- Third, I assume a writer-and-reader-friendly solution to the pesky problem of ANDs and ORs having no precedence in natural language.[1]

Given these basic caveats, by 'being unambiguous' I mean removing ambiguity beyond a reasonable doubt in formal communication including rules.

Here is a simple example of the kind of ambiguity that policy interpreters, business analysts, and IT professionals deal with daily. It's a sentence from the California 2014 Paid Sick Leave Policy.[2]

Accrued paid sick leave shall carry over to the following year of employment and may be capped at 48 hours or 6 days.

Ambiguities:

- What is being capped? Is it the amount of accrued paid sick leave in a given period or the amount of sick leave that may be carried forward?

- What is meant by "may be"? … Must be? … Can be but need not be?

These ambiguities must be wrung out of the statement to get a clear interpretation (i.e., unambiguous beyond a reasonable doubt).

As illustrated above, the key to disambiguation is forming the right questions to ask. A good reader of formal messages 'sees' the questions that should be asked. A good writer of formal messages avoids them in the first place.

Disambiguation is a fundamental skill for policy interpreters and professional analysts of all stripes — indeed, for any writer of formal communications. This discussion illustrates disambiguation using two typical examples.

Example 1

Consider this statement:

An order must not be shipped if the outstanding balance exceeds credit authorization.

On a quick first reading this statement might seem clear enough. Look closer, however, and the meaning becomes murky. Important clarifications are missing or hidden from view.

- Outstanding balance of what? The what might be order, customer, account, shipment — or something else altogether.

- Credit authorization of what? Again, the what might be order, customer, account, shipment — or something else.

To disambiguate the statement, suppose you pursue these questions and discover that:

- account has outstanding balance

- account is held by customer

- customer places order

- customer has credit authorization

How do you find these things out? Hopefully, your concept model informs you. No concept model? You need a blueprint, so time to start building one now.[3] You're likely to come across the same ambiguities time and time again.

Using the clarifications, the ambiguities in the statement can be eliminated. The result is the following (new portions underlined based on the discoveries above):[4]

An order must not be shipped if the outstanding balance of the account held by the customer that places the order exceeds the credit authorization of the customer.

The statement has now been disambiguated beyond a reasonable doubt. Of course, that assumes the meanings of the terms it includes are agreed, but that's another purpose of creating a concept model. The statement now makes deep sense, sufficient for formal messaging. In other words, it is practicable.

Example 1 highlights some very important points about rule analysis.

- The central activity is interpretation. You take statements that are less than fully clear and interpret them into statements that are more fully clear. A key skill for this kind of interpretation is the ability to disambiguate.

- Interpretation happens just about everywhere in business and government. It is a key component of how business capabilities are operationalized.

- Recording acts of interpretation (who interpreted what, when, in what ways, and for what reasons) is central to traceability, good business governance, and corporate memory.[5]

Example 2

This second example is a bit more complicated. It's from a client in the mortgage industry.

Income must be greater than 20% of the estimated value if subject to litigation.

Questions that arise in interpreting this sentence include:

- Income of what?

- Estimated value of what?

- What is subject to litigation?

Since the subject matter pertains to loan applications, it's a safe bet that the sentence pertains to property. Unfortunately, as happens so often in informal messaging, that context has been assumed in the sentence. So, if that's correct, property should be referenced explicitly.

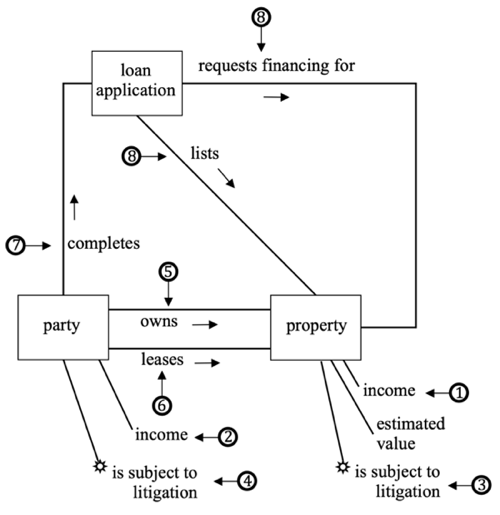

How things are related in mortgage knowledge is complex, so at this point we won't make much progress without a blueprint to go by. Figure 1 presents a partial concept model diagram to help out. Lines in the diagram have been numbered to assist in the subsequent discussion.

Figure 1. Concept Model Diagram Supporting Loan Applications

Here's a quick explanation of the notation.[6]

- Boxes labeled by appropriate terms represent noun concepts.

- Lines represent verb concepts (so facts and rules can be expressed).

- Arrows beside lines between boxes indicate which direction to 'read' the wordings for verb concepts.

- Lines without explicit wordings to unboxed terms default to the wording 'has'.

- Lines with sunburst symbols at one end represent unary verb concepts (which evaluate only to true, false, or unknown for any given party or property).

Now let's focus on disambiguating the original sentence. We can see from the diagram that estimated value pertains to property. That much is clear. But several ambiguities are now apparent for the sentence:

- Income could pertain either to property (1) or to party (2).

- Property is subject to litigation (3), but so is party (4).

Disambiguation requires resolving these ambiguities — in other words, clarifying which income the sentence refers to and what is subject to litigation.

Let's focus on the former ambiguity first. Which income is being talked about? And in what way does income relate to property? Review of the diagram reveals more potential resolutions than you might imagine — at least five. These resolutions are expressed below using relevant wordings for the respective verb concepts:

- The income (1) is of the property.

- The income (2) is of the party who owns (5) the property.

- The income (2) is of the party who leases (6) the property.

- The income (2) is of the party who completes (7) a loan application that lists (8) the property (as collateral).

- The income (2) is of the party who completes (7) a loan application requesting financing for (8) the property.

Picking the right answer is a matter of knowing the business knowledge. Subject matter experts will tell you that resolution 5 is the correct interpretation. They also will clarify that the sentence pertains to property being subject to litigation, not party.

Now wordings for the relevant verb concepts can be worked into the sentence to remove ambiguity beyond a reasonable doubt (wordings underlined):

The income (2) of the party who completes (7) a loan application requesting financing for (8) a property must be greater than 20% of the estimated value of the property if the property is subject to litigation (3).

Assuming the terms are properly defined, the rule is now practicable — complete and ready for prime time.

References

[1] Does 'A and B or C' mean '(A and B) or C,' or 'A and (B or C)'? The problem has a perfectly workable solution. See Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: Using "The Following" Clause, URL: https://www.rulespeak.com/en/RuleSpeak Tabulation Primer.pdf

[2] https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/publications/paid_sick_days_poster_template_(11_2014).pdf

[3] Refer to Business Knowledge Blueprints: Enabling Your Data to Speak the Language of the Business (2nd ed), by Ronald G. Ross, 2020.

[4] We use the RuleSpeak® guidelines to express rules: www.RuleSpeak.com. Think of RuleSpeak as an interpretation disambiguator. It supports building a common communication community among business people, business analysts, and IT professionals for textual rules.

[5] Refer to Business Knowledge Messaging: How to Avoid Business Miscommunication, by Ronald G. Ross, 2022, Chapter 9.

[6] For detailed explanation of the notation refer to Business Knowledge Blueprints: Enabling Your Data to Speak the Language of the Business (2nd ed), by Ronald G. Ross, 2020.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules